Introduction

In the late 1980s, the distribution of the world’s countries and the world’s people resembled a ‘twin peaks’. The global distribution showed a hump at the poorer end (encompassing the countries and people living in the homogenous ‘Third World’), a hump at the upper end (developed countries and their population), and weak prospects for convergence of the poorer group with the richer one.

Since the end of the 1990s, that twin-peaks world with a poorer and a richer peak transitioned into what might be labelled the ‘new middles’ (or ‘twin middles’) of countries and people of the contemporary world.

The first ‘middle’ refers to countries and is an expansion of the number of those officially classified by the World Bank as middle-income countries (MICs). The second middle comprises the burgeoning group of people who consume at levels above the global poverty lines ($1.90 and $3.30-per-day) used by the World Bank. A large proportion of them, however, are still living well below the consumption lines associated with a permanent escape from poverty ($13-per-day). The following paragraphs will initially discuss the first middle, referring to countries, and subsequently elaborate on the second middle, comprising people.

The first new middle of Middle-Income Countries

As noted, the first new middle – that of middle income countries – is the official classification by the World Bank. Some countries are substantially above the World Bank’s middle-income line, particularly the populous developing countries of China and India, whilst other developing countries are closer to the line. During the 2000s, the number of LICs started falling to less than 30 LICs today. The number of HICs (which currently are countries with approximately US$12,500 GNI per capita, Atlas method) has doubled from about 40 in 1990 to over 80 today.

At this point, one could simply dismiss all of this as a set of arbitrary lines, as indeed one could do with the declines in global poverty. However, as much in need of review as the Low/Middle/High income country (LIC/MIC/HIC) lines are, they do have symbolic meaning in terms of greater policy freedom in the form of greater access to larger amounts of non-concessional finance from not only from the World Bank and IMF but also in the form of bond issues in private capital markets (which in contrast to donor conditionality are without strings). Also, as crude as these lines are, they are, in the broadest sense, an aggregation of other development indicators, since cluster analysis places all the remaining LICs in one homogeneous cluster. In fact, one justification for the continued use of these lines is that the remaining LICs are now relatively homogeneous in terms of their structural economic characteristics and a shared (weak) recent growth history. Moreover, almost all are members of the United Nations (UN) grouping of least developed countries (LDCs).

The new MICs, in contrast, are heterogeneous. They include many fast-growing ‘emerging economies’ where manufacturing-led growth is evident, such as China, though the 2000s commodity boom was also important as much as manufacturing in other countries such as Indonesia and Brazil. Many of these populous new MICs are home to a large proportion of the world’s absolute poor at all poverty lines. Some other countries, formerly planned economies, are ‘bounce- back’ new MICs that experienced economic collapse in the past but have grown back to MIC levels since.

The second new middle of people

The second new ‘middle’ is that of people living just above absolute poverty and at risk of falling back. Global poverty has fallen when measured at the World Bank’s extreme poverty line of $1.90 per day and moderate poverty line of $3.20 per day. However, outside of China, the fall in the number of people living in poverty is more modest. Moreover, many of these people are still well below consumption lines associated with a permanent escape from poverty which longitudinal studies estimate to be at approximately $13 per day in 2011 PPP based. This ‘security from poverty’ line can – very broadly – be seen as the line at which people are very unlikely to fall back into poverty at approximately $3.20-per-day. In other words, the risk of falling back below this line diminishes to very low probability above $13-per-day. This means that there is a substantial group of people living above the global poverty lines for absolute poverty but not sufficiently far to be certain of not falling back into poverty in the future. When taking a poverty line of $13 per day, global poverty has not changed that much since the late 1980s. Global poverty measured at $13 per day has fallen from about 90 per cent of the developing world population in the 1980s to about 85 per cent in 2015. However, when China is excluded from these estimates, little has changed since the 1980s in the sense that 90 per cent of the population of the developing world outside China remain in poverty.

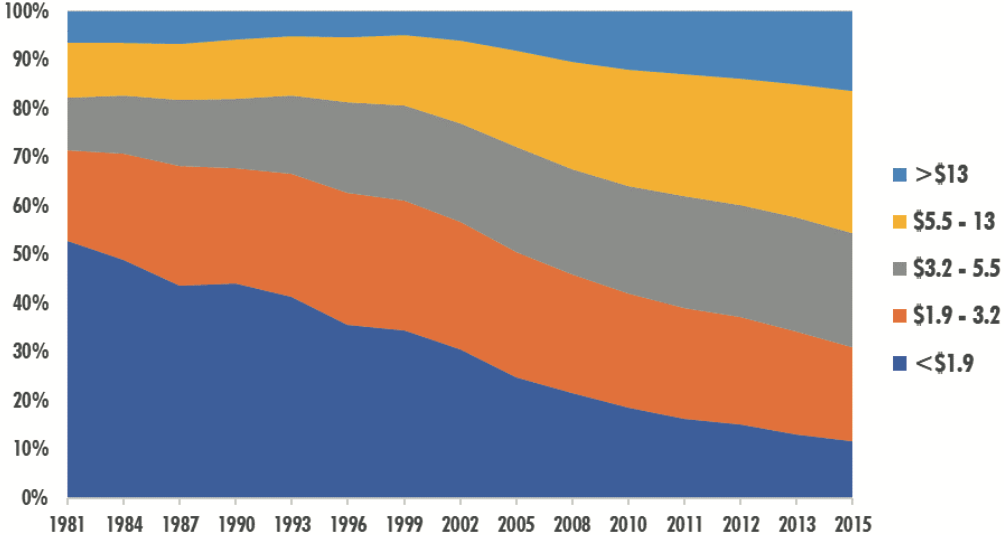

What has happened is that those moving out of poverty measured at $3.20 per day have not jumped in one leap to living above $13 per day. Instead, they have moved into the precariat group with incomes between $3.20 and $13-per-day (see Figure 1). This in- between poverty and security group has grown from 20 per cent of the developing world’s population in the early 1980s to about a half in 2015. In short, in 2015, a third of the population of the developing world lived in absolute poverty (under $3.20) and approximately one in nine or ten were secure (over $13), leaving the remainder – over half of the developing world’s population – in a precarious new middle (between $3.20 and $13 per day). This is a second new middle, of people who are neither day-to-day poor nor secure from the future risk of poverty.

To be clear, this is not to say that the income growth among the poorest people in the world has not been positive. The issue is that setting very low poverty lines and communicating the trends based on these lines may lead to a narrative that absolute poverty is virtually eradicated or soon will be. What is presented in poverty measurement as a technical issue is actually highly political. Global poverty reduction since the Cold War has been mostly about moving people from below to somewhat above a low poverty line. Highlighting this trend often ignites tempers and fierce debate but one cannot overlook the fact that absolute poverty has not fallen at more reasonable poverty lines, even with the impressive income growth in developing countries during the past two decades.

In short, what has happened in the developing world since the Cold War is a large movement of people into what could be called a precariat ($3.20–$13). Poverty has fallen when measured at the $3.20 line from approximately 70 per cent in 1981 to 30 per cent in 2015. Consequentially, a new middle has burgeoned of a population living on between $3.20 and $13 which by 2015 accounted for over half of the developing world’s population. One could liken this to a transition from global poverty towards global precarity.

The potential impact of COVID-19

In sum, substantial economic growth since the Cold War has thus produced two new ‘middles’. Specifically, a new middle of countries which are now middle-income according to average per capita income and a new ‘middle’ of people, lifted above absolute poverty, at least when measured at low poverty lines, but who are not sufficiently far above as to be certain of not falling back into poverty.

These gains are now at risk due to the economic impact of COVID-19.

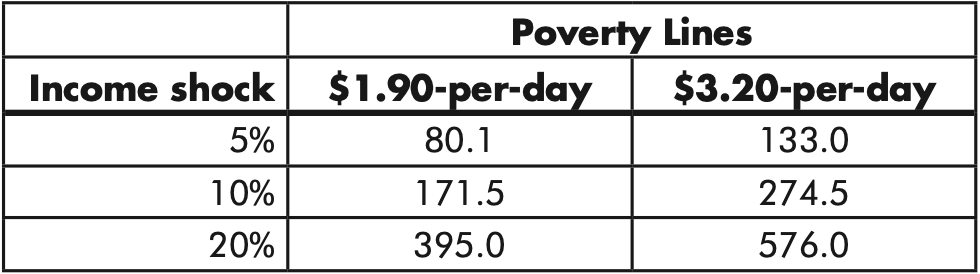

Indeed, the pandemic is very likely to push people back into poverty. Estimates suggest between 80m and 400m people could fall back into extreme poverty due to the pandemic; and up to 600m could fall back into poverty at the moderate poverty line (see Table 1). These numbers represent a reversal of 20–30 years in global poverty reduction (depending on whether one takes absolute or relative counts).

This why COVID-19 is such a threat to the progress achieved to date. Too little attention is being given to the worsening crisis in developing countries where coronavirus is spreading rapidly and governments grapple with the devastating economic consequences.

The attainment of SDG 1 goal is looking increasingly tough due to COVID-19.

In addition to increases in the poverty headcount, the intensity and severity of poverty are also likely to be exacerbated too. The daily losses could be in the millions of dollars per day among those already living in extreme poverty, and among the group of people newly pushed into extreme poverty as a result of the crisis.

There could be much more new poverty not only in countries where poverty has remained relatively high over the last three decades but also in countries that are not among the poorest countries anymore.

The pandemic itself raise questions for how we think about poverty reduction and in particular, the need for new measures of extreme precarity to sit alongside measures of extreme poverty. The extreme poverty measure ($1.90) gave a poverty count of about 700m or 9.9% the world’s population before the crisis. Just above those people sit another 400m people or 5.4% of the world’s population living in extreme precarity, one shock away from poverty whether it is this wave or the next wave of COVID-19.

Figure 1. Population (%) of developing countries living by daily consumption group, 1981–2015. Source: Authors’ estimates based on World Bank (2020).

Table 1. The Poverty Impact of COVID-19: Increase in global poverty at $1.90 and $3.20-per-day poverty lines (millions of people) due to 5, 10, and 20 percent per capita income contraction

References

Sumner, A., Ortiz-Juarez, E., and Hoy, C. (2020) Precarity and the pandemic: COVID-19 and poverty incidence, intensity, and severity in developing countries. UNU-WIDER Working Paper. UNU-WIDER: Helsinki.

World Bank (2020). PovcalNet. World Bank: Washington, DC.

This article is an extract taken from the Parliamentary Network publication ‘Just Transitions’. You can download a pdf version of the full document here.